|

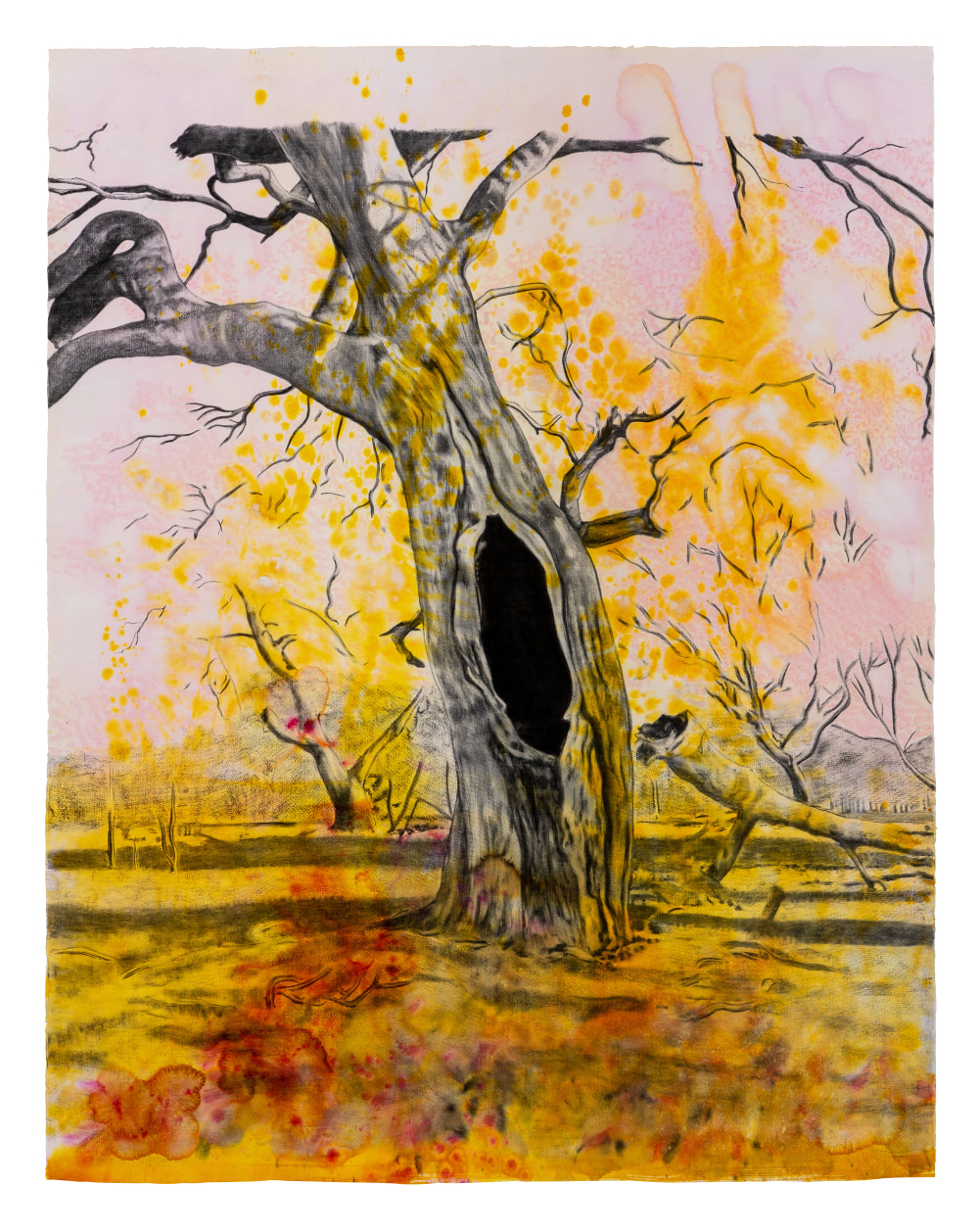

Echo in the Hollow, an exhibition of drawings inspired by the biyal*

2 November 2023 – 4 February 2024 “The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way.” William Blake, 1799. The local river red gum is called biyal* in Dja Dja Wurrung language. It lives, reproduces and dies along creek lines, intermittent watercourses, swamps, billabongs, flood plains and inundated man-made water catchments. They rarely grow far from a watercourse, so if you take the time to observe, an old tree tells much about the history of country beneath its roots, from initial animal pathways to water flows and the activity of life. They live 500 to 1000 years, grow to 14 metres circumference and can be up to 40 metres high. First Nations people say they think of them as members of the family, providing food, medicine, vessels, shields and shelter, living many human generations. Thus they share stories marked in their limbs and trunks over centuries. In the 18th Century the colonial invasion of Australia began. We killed many of the trees by clearing and cutting them for furniture and firewood rather than harvesting their living bounty. In the 20th Century water catchments were created which drowned great tracts of Bial along creeklines and rivers. But even the long-dead Bial provide shelter and habitat for fish, birds, reptiles, mammals, bees and many other invertebrates. In some parts of Australia there are projects underway to record carved trees before they tumble. ‘Plant blindness’ is a term used for our inability to see or notice the plants in our own environment, as if they were just wallpaper to our lives. It is particularly common in developed countries and affects the way we care for the world around us. Trees cool the climate around them and aid biodiversity as well as providing oxygen. Telling stories about trees helps evoke empathy for them and in doing so it helps us. Many of my works are tree portraits as distinguished from landscapes. In this series I have been interested in the biomorphic patterns created by long-dead trees. Mirroring some images creates potentially reversible scenes - but what acts are reversible in our environment? I am also interested in reflections and duality in the world of the psyche and in anthropomorphising the gestures of trees. These trees, some mirrored, some morphing into creature-like forms through nature’s intervention - scars, carvings and patterns - spread tendrils which intertwine and puncture the intense hues in the water and sky like the viscera of our bodies. I draw attention to the tree, its significance and symbolism via myth in cultures throughout history, and begin to make a record of those closest to me on Dja Dja Wurrung Country. From ancient stories of the tree of life to the local tales of men who became trees along our creek lines - there are many ways of seeing a tree. ~ Tiffany Titshall, 2023 *biyal in Dja Dja Wurrung language is the name for the local River Red Gum. Pictured: This Tree Lives, 2023. acrylic, ink, pencil and charcoal on paper. 181 x 153 cm (unframed)

0 Comments

|

Majorca StudioIn the studio and other places. Tiffany Titshall works in charcoal on paper from her studio in central Victoria. From landscapes and follies to darker, more overt images of animals and devils, her work always simmers with hints of her inner world.

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed